Destinations

Experiences

|

L A

D A T C O T O U R

S |

|

||||||||

| HOME | South America | Falkland Islands | Antarctica | Unique Destinations |

Unique Experiences |

Newsstand | ||||

|

|

The Inka Trail Inca Trail Route Map Sample 4-day/3-night itinerary Chicago Tribune Article

|

|

|

By John Biemer, Chicago Tribune staff reporterRacing the sun on the Inca Trail

January 30, 2005

MACHU PICCHU, Peru -- When the park entrance opened at 5:30 a.m. sharp, we began a full-steam-ahead sprint as far as our lungs and the uphill trail would let us, our backpacks bouncing and our bamboo walking sticks clicking on the irregular stony path.

Compared to the three grueling days of high-altitude trekking that led up to this, it was just a brief final push, but it was no cakewalk, and the drop-offs along the side of the trail were some of the sharpest we'd seen. Fifteen minutes later, the sun's halo appeared over the distant mountaintops, and we wondered if we were doomed to miss the climax of our trip.

We already were winded when the trail led to a set of "monkey steps," so steep and crooked that it's best to lean forward and use your hands to steady your climb. We scurried up, giddily thinking they marked the end. They didn't.

Pushing forward around a bend, we reached an ancient stone structure: Intipunku, the Sun Gate. From this summit, we peered down as sweat dripped down our foreheads. It was 6 a.m., and the shadows of the surrounding peaks were receding to unveil a postcard view of the crown jewel of the Inca empire: Machu Picchu.

My wife, Joanne, and I had made it with barely a minute to spare, sharing the November sunrise with just a handful of other hikers. Soon we were joined by 50 more, who scrambled to fish cameras out of their backpacks and begin clicking away.

***

The Inca Trail isn't for everyone--you can reach the mysterious lost city by a combination of buses and trains, and there's a luxury hotel on the same mountainside. But there's probably no more rewarding way to prepare for the glory of Machu Picchu than taking the four-day, 26-mile journey, soaking in views of the towering Andes and learning firsthand the historical, architectural and geographical context that makes it such a phenomenon.

Technically, the trail begins in Cuzco, once the center of Incan civilization and South America's oldest continuously inhabited city. But most treks kick off farther along at Kilometer 82, where a wooden footbridge crosses the muddy Urubamba River. It's rugged, barren terrain at first. Cactus and giant boulders line the path, which we share with livestock and children in Catholic school uniforms.

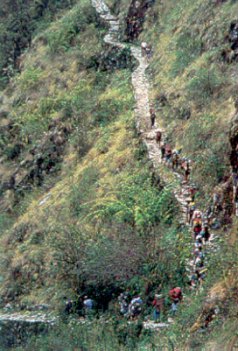

Our group consists of two guides, 15 trekkers and at least that many porters. We begin at about 9,100 feet, but the rigorous roller-coaster trail will take us almost 5,000 feet higher before we end up at Machu Picchu, the lowest point at about 7,900 feet.

Twenty minutes into the walk, we stop by the river. "Time to eat coca leaves," announces our lead guide, Margareth Farroc, a Cuzco native. We pull out baggies of the leaves--legal in Peru, though they're used to make cocaine--that we'd purchased for a dollar from a little old lady in the tourist hamlet of Ollantaytambo where we'd spent the night before. But first, Margareth asks us to pick out the three best leaves and place them on a boulder as an offering for the Inca mountain gods to beseech them to look after us on the trail.

"Please feel the energy of the nature, the mountains, the river, the mother earth," she says, imploring us to keep a positive attitude. "Machu Picchu is behind many, many mountains."

The dry leaves settle into a wet wad in our cheeks. Some notice numbness on the edges of their tongues. "I prefer the tea over the leaf," one Canadian traveler says, referring to the omnipresent mate de coca, which we've been drinking to ease altitude symptoms.

A short time later, Margareth signals the group to stop again, and plucks some white powdery berries from a cactus. She rubs them together until they create a purplish dye, known as cochinilla, which is used to dye alpaca wool. With a stick, she paints tattoos on our arms of Inca symbols: the condor, the sun, a flower, a snake.

Two hours later, we pause for a breather at the first Inca ruins on the trail, an outpost with neatly tiered terraces overlooking the river. Machu Picchu may be the most impressive of the settlements, but it's not the only one. Far from it. In the coming days, we'll visit about a half-dozen more of these scenic ruins that were hidden by the mountains for centuries.

With the words "history, please," Margareth begins to teach us about their precise stone-cutting and masonry, and the typical layouts from the terraces and complex irrigation systems to the sacrificial altars in the temples of the gods.

At lunch time, we find the porters have arrived well ahead of us and set up a dining tent. We settle in, elbow to elbow, on small foldable canvas stools for a hot, family-style meal of tomato soup, chicken and half an avocado, finished off with coca tea.

The porters, we quickly learn, are the true heroes of any Machu Picchu trek. As sure-footed as mountain goats and with Inca blood coursing through their veins, they carry on their backs 55-pound sacks--including most of our personal belongings, the tents and dining supplies--as they pad up and down the trail at breakneck speed. Their battered, swollen toes tucked into rubber sandals testify to their hard labor.

After lunch, we enter the rain forest. Ferns, orchids and passion flowers poke from the increasingly thick, green foliage. Bromeliads hang from trees, and hummingbirds twitter by. Then the trail begins a relentless 2,600-foot ascent. We grill Margareth. Hadn't she told us the first day was "flat"?

"Inca flat," she says, amending her description.

The campground that night, at an altitude of 12,500 feet, is above most of the trees, and provides a breathtaking view of the sky-high Andes. The porters already have erected our tents, and they hand us hot tea as we drop our packs in exhaustion.

Over dinner, we pour Peruvian rum into our hot chocolate, trade jokes and play drinking games. The porter chef presents a cake for a Canadian woman's 50th birthday (our group ranged in age from 23 to 50).

When we unzip our tent the next morning, llamas are outside, grazing on the brush. Misty clouds envelope us as our second day of hiking begins with a steep 1,300-foot climb. The elevation really kicks in here, and we stop often to catch our breath. Some of us have tingling in our fingers and toes--another altitude symptom.

We break for water and chocolate at Dead Woman's Pass. At about 13,900 feet, it's the highest of three passes on the trail. Then it's down, down, down a gigantic, knee-hammering stone staircase. Some of the steps are smaller than our feet.

The third day, considered the most beautiful on the trail, is a relatively moderate five-hour hike through lushly forested, lower altitude mountains. But rolling clouds mostly block our view, so after we splash our faces in a fountain at the well-preserved ruins of Phuyupatamarca ("town above the clouds"), we concentrate on the trail--particularly another 2,000 steps down.

We stop for the day at 1:30 p.m. at a campsite one mountain away from Machu Picchu, and a short stroll from Huinay Huayna, another small but gorgeous Inca village where bright red begonias sprout from cracks between the stones.

On the last night, we tip our porters and salute them with a song a fellow trekker wrote over dinner. They return the favor with songs in their native Quechua language, and we complete this cultural exchange with a rendition of "YMCA."

Our visit to the gods at Machu Picchu begins with a wakeup call at the ungodly hour of 3:45 a.m. A porter shouts "Buenos dias!" into our tent, and an astonishing number of stars light up the sky as we groggily force down some warm oatmeal and pancakes. When we emerge from the dining tent, the mountains appear as ghostly silhouettes against the dark, navy blue sky.

Using flashlights, we bumble through a five-minute walk to the park entrance and wait for that 5:30 opening. Rangers have established that hour to prevent people from hurting themselves on a pitch-black trail, but Margareth is determined that we be first in line so we can make it to the Sun Gate in time.

We don't let her down. As scores of hikers line up behind us, the sky brightens and we put away our flashlights. The characteristics of the Andes emerge, the sheer cliffs, the dense green growth and the craggy snow-capped peaks in the distance. Classic photos of Machu Picchu show it draped in clouds, and Margareth says many of her tours end drenched in rain. But the only rain we'd had along the trail was at night, and the skies could barely be clearer for our final dash.

"Honestly, honestly, this week we have good luck, really good luck," Margareth says later, as she began her final lesson standing on a Machu Picchu terrace. "Every day, we had sun, sun, sun. Good offerings, guys. Thank you for this. You give to nature, and nature gives to you."

E-mail: jbiemer@tribune.com

Copyright (c) 2005, Chicago Tribune